You saw this same list (shortened) before the French Open.

You saw it before Wimbledon.

Now, you get to see it before the U.S. Open.

Just so I don’t get any hate mail or hate tweets, this is not a list of the greatest U.S. Open matches of all time. Significance and greatness certainly intersect at times, but they are ultimately not one and the same thing. With that word of clarification in print, let’s move to the list:

*

10 – 1968 FINAL: ARTHUR ASHE d. TOM OKKER, 14-12, 5-7, 6-3, 3-6, 6-3

The Open Era began in 1968, so Ashe was naturally the first African-American to win a men’s singles title in the era.

He remains the only one to do so.

Beyond the barriers he broke in tennis, Ashe was a legitimately great player. He won three majors, one at each of the non-clay major tournaments. The fact that Okker, his formidable Dutch opponent, made him work so hard for his only U.S. Open championship adds to the luster of this event.

As a historical footnote, the 1968 U.S. Open marked the beginning of the tournament’s longstanding association with CBS Sports, a marriage that will end with the conclusion of this year’s tournament. ESPN becomes the lead broadcaster next year.

9 – 1970 FINAL: KEN ROSEWALL d. TONY ROCHE, 2-6, 6-4, 7-6 (2), 6-3)

There’s never a bad moment in which to sing the praises of one of tennis’s most overlooked great players.

Ask yourself: Among ATP major champions who played in the 1970s or later, is there a quieter, less trumpeted eight-time major champion (or better) than Ken Rosewall? Roy Emerson played singles at the majors through 1971, and he claimed 12 major titles, but six of them were in Australia, and none came after 1967, when Emerson was still 30 years old. Rosewall didn’t win as many majors as Emerson, but he remained a vital and substantial force in professional tennis well after the transition from the Amateur Era to the Open Era in 1968. In our list of the 10 most significant Wimbledon men’s singles matches of all time, we noted that Rosewall made Wimbledon finals 20 years apart, in 1954 and 1974. Rosewall was 39 in 1974.

At the U.S. Championships/U.S. Open, Rosewall forged a similar legacy of longevity. He won the tournament for the first time in 1956. Yet, there he was 14 years later in 1970, stopping Tony Roche in four sets. Emerson and many of Rosewall’s contemporaries, from Australia or not, could not match his staying power on tour.

A small but real measure of added historical significance can be found in this match as well: It was the first major singles final to involve the use of a tiebreaker. The U.S. Open was the first major to adopt Jimmy Van Alen’s invention. Unsurprisingly, the U.S. Open — historically wedded to the tiebreaker as it was — then became the one major to use a final-set tiebreaker. There has never been a U.S. Open men’s singles final decided by a fifth-set tiebreaker (thank goodness).

8 – 1936 FINAL: FRED PERRY d. DON BUDGE, 2-6, 6-2, 8-6, 1-6, 10-8

In 1933, Perry won the first of his eight major titles by winning the U.S. Championships over Jack Crawford of Australia, a fine player in his own right. However, Perry’s last major championship was won in the face of resistance from Don Budge, a man considered among the greatest in tennis history. Either match would deserve inclusion on this list, but in the interests of avoiding duplication, the 1936 final gets a slight nod over 1933.

*

7 – 1925 FINAL: BILL TILDEN d. BILL JOHNSTON, 4-6, 11-9, 6-3, 4-6, 6-3

Before Ivan Lendl made eight straight U.S. Open finals from 1982 through 1989, Big Bill Tilden made eight straight from 1918 through 1925.

What applies to Fred Perry (above) applies to Big Bill Tilden as well. You could just as easily pick another one of his U.S. Championships triumphs — specifically, the 1929 final, won against Francis Hunter in five sets — as a hugely significant match. The 1929 final is significant for Tilden because it marked his seventh and last U.S. Championships title. As a point of comparison, Roger Federer, Pete Sampras, and Jimmy Connors have all won “only” five U.S. Opens. Tilden’s 1929 title came four years after his previous one, showing how much of an enduring presence Tilden was throughout the 1920s. However, Tilden’s sixth U.S. title in 1925 was in many ways a crowning moment for him.

The 1925 final marked Tilden’s eighth straight U.S. final, a feat Ivan Lendl matched in the 1980s by making the 1982 through 1989 finals. It also marked a situation in which Tilden was gunning for a sixth straight championship, the situation Roger Federer failed to handle in the 2009 final against Juan Martin del Potro. Tilden was also facing a frequent final opponent. Bill Johnston had met Tilden in four of the previous five finals, and this would turn out to be his last shot at Tilden. Johnson had actually defeated Tilden back in the 1919 final, but he didn’t want that victory to be his only taste of glory against his foremost U.S. Championships rival.

Tilden received Johnson’s best shot on that day, nearly 90 years ago. Yet, for the third time in the past six finals, Tilden captured the fifth set to take home the trophy. You could very legitimately choose his 1929 victory, but the verdict here is that the 1925 U.S. title is the one which carries the most significance as far as Tilden’s legacy is concerned.

6 – 1981 FINAL: JOHN McENROE d. BJORN BORG, 4-6, 6-2, 6-4, 6-3

This match might seem to be hugely undervalued in terms of its significance — perhaps. Yet, it feels like a match that has been talked about more than its actual historical weight. It’s true that this was Borg’s last U.S. Open final and his last major final. It’s true that this was yet another loss in New York at a tournament he never won, which couldn’t have made the legendary Swede very happy. Yet, there’s another U.S. Open final which represents more of a missed opportunity for Borg, and that’s the biggest reason why this entry is only sixth on the list.

That other match is next:

*

5 – 1976 FINAL: JIMMY CONNORS d. BJORN BORG, 6-4, 3-6, 7-6 (9), 6-4

Bjorn Borg had his chance to win the U.S. Open on clay in 1976, but he couldn’t solve Jimmy Connors. When the tournament moved to hardcourts a few years later, Borg wasn’t able to deal with John McEnroe’s attacking style, which was enhanced by the faster surface at the USTA National Tennis Center.

The U.S. Open that truly got away from Borg (even though he led McEnroe by a game in the fifth set of the 1980 final) was the 1976 event. Why is this the case? From 1975 through 1977, the Open was played on green clay — not as slow as the red clay of Paris, but not hardcourt, either. Borg’s inability to take a pivotal third-set tiebreaker in a tied match ultimately cost him. Had Borg won this 1976 event, not only would he have gained confidence in his ability to handle his opponents; he probably would have learned how to handle New York a bit better, settling into a comfort zone in a city that was diametrically different from his own quiet demeanor. This trumps 1981 and 1980 in terms of Borg’s most difficult U.S. Open losses, though reasonable people can — and surely will — disagree.

4 – 2010 SEMIFINAL: NOVAK DJOKOVIC d. ROGER FEDERER, 5-7, 6-1, 5-7, 6-2, 7-5

The 2011 semifinal between these two men is probably remembered by more people, due to “The Shot,” Djokovic’s go-for-broke first-serve return down two championship points at 3-5 in the final set. However, the 2010 match is the more significant semifinal, albeit by a narrow margin.

You’ll notice that no Federer-Nadal-Djokovic-Murray matches have yet made the list. They’re being brought to the front, but they can’t all occupy this list. Otherwise, this list would really be just a 21st-century list, not a full survey of tennis history. Accordingly, a lot of Fed-Rafa-Nole-Muzz matches have to be left on the cutting-room floor. The 2011 Federer-Djokovic semifinal is one of them. The 2008 Federer-Murray final is another, the 2012 Murray-Djokovic final another, the 2013 Nadal-Djokovic final still another. (There are, of course, even more matches that didn’t make the cut. In a top 20 list, they would have.)

The 2010 Federer-Djokovic semifinal is exactly like the 2011 semi in that Federer was one point away from facing Rafael Nadal at the U.S. Open for the first time, specifically in the final. It’s one of the great empty spaces in tennis history: the Federer-Nadal rivalry has never been enacted at Arthur Ashe Stadium. Nadal’s withdrawal this year ensures that the two men can’t meet until 2015 at the earliest, with the clock ticking on Federer’s career.

Beyond that similarity, though, the 2010 semifinal acquires more importance than the 2011 edition because this is the match that truly:

A) launched Djokovic’s transformation, which emerged in full flower in 2011, capped by his U.S. Open win (and aided principally by “The Shot” in that aforementioned semifinal against Federer);

B) shifted the balance of power in the Federer-Djokovic rivalry, by giving Djokovic a level of confidence that had been missing when he lost to Federer at the U.S. Open in 2007 (final), 2008 (semis) and 2009 (semis).

Had this 2010 semifinal gone the other way, it’s highly doubtful that Djokovic would have produced one of the great individual seasons in history in 2011. It’s also doubtful that Djokovic would have as many as seven majors today.

As for Federer, it’s true that he responded to this wrenching loss by knocking off Djokovic in the 2011 Roland Garros semifinals. Yet, Djokovic was the one who reached the mountaintop in 2011, and when Federer — hobbled by injury in 2010 at Wimbledon, where he bowed out in the quarterfinals — couldn’t win a main-event match several weeks later in New York, his career stalled.

Phrased differently, if Federer wanted to show that his prime period (which began late in 2003) had not ended, the 2010 loss to Djokovic put an end to that particular aspiration.

*

3 – 2010 FINAL: RAFAEL NADAL d. NOVAK DJOKOVIC, 6-4, 5-7, 6-4, 6-2

Rafael Nadal finally won the U.S. Open in 2010 after several years in which he came up short. Nadal completed the career Grand Slam at the age of 24, a testament to how great he was in the early and early-middle stages of his career.

This match completed several circles for Nadal while initiating others in the current era of men’s tennis. The 21st century has witnessed Federer’s 2005 and 2006 and Djokovic’s 2011, three of the most dominant seasons men’s tennis has ever known in the Open Era. Rafael Nadal’s 2010 belongs alongside those other seasons, and the fullness of Nadal’s achievements was cemented with this championship conquest over a determined but not-quite-ready Djokovic in a superb match. Djokovic had just taken down Federer in a match whose significance couldn’t have been known (not in its entirety) at the time. In the final, he had to turn around and face an in-form Nadal, and the challenge was far too much for the Serbian who — while still playing well — would need a few more months in which to put all the pieces together in his career.

Nadal’s 2010 U.S. Open marked the year in which the greatest clay-courter of all time played his best hardcourt major of all time. The 2009 Australian Open was Nadal’s first hardcourt major, and it featured the Spaniard at his most resolute. Nadal won that tournament on grit and hustle. The 2010 U.S. Open was claimed with authoritative power, as a server and in every other aspect of stroke production. Nadal hammered his first serves with conviction; he never served better at a major than in the 2010 Open. By successfully flattening his groundstrokes — something he had always needed to do on a hardcourt — Nadal achieved a fundamental transformation that had previously eluded him in New York.

The result: a career Grand Slam, something only six other men had done (Perry, Budge, Emerson, Rod Laver, Andre Agassi, Federer), and something only three other men (Laver, Agassi, Federer) had achieved in the Open Era.

What’s also significant about the 2010 U.S. Open final is that it would motivate Djokovic to step up his game against Nadal, something he did with great success through the 2012 Australian Open final, including the 2011 U.S. Open final, when the Serb avenged his 2010 loss. This match set in motion the riveting years of the Nadal-Djokovic era in major tournament finals, one of a few central showcases in this marvelous era of men’s tennis.

2 – 2004 QUARTERFINAL: ROGER FEDERER d. ANDRE AGASSI, 6-3, 2-6, 7-5, 3-6, 6-3

Federer has won five U.S. Opens, but none of his wins in finals carry the significance of this match, because without his victory over Agassi in 2004, the Swiss might not have become such a giant in the sport. Federer’s 2004 required an escape in the Wimbledon final, one of the turning-point moments that filled him with a belief that he could overcome any obstacle on court. This was the other major escape in Federer’s 2004 season at the majors.

Federer had never won a U.S. Open as he came to New York in 2004. As the reigning Wimbledon champion a year earlier in 2003, Federer was dismissed by early-career nemesis David Nalbandian in the fourth round at the Open. You can never know for sure that you can win in a given tournament until you pass a defining test. For some, that test is the final, but in 2004, the big hurdle for Federer was his quarterfinal against a proven and beloved champion who owned the allegiance of the Ashe Stadium crowd.

This match started before a buzzing late-night crowd but was suspended due to rain. Federer had won a close third set before the suspension of play, but when the match resumed on a windy afternoon and Agassi — regularly a great wind player because of his compact strokes — swiped the fourth set, the contest was a complete toss-up. Federer had not yet developed his aura of invincibility, especially not in New York. He did not have the crowd on his side, a marked contrast from the present day. The only time Federer is not the crowd’s favoritte these days is when his opponent is a host-nation player (and even then, he gets a warm reception from fans).

Federer was playing the crowd, the wind, and Andre Agassi in that fifth set on an afternoon that felt much more like autumn than summer in the Big Apple. The Swiss prevailed, and if there were any doubts about the importance of the match, Federer let out a primal roar and ripped at his shirt right after he won match point.

The rest of that U.S. Open — and Federer’s U.S. Open career in general — took off from that point.

*

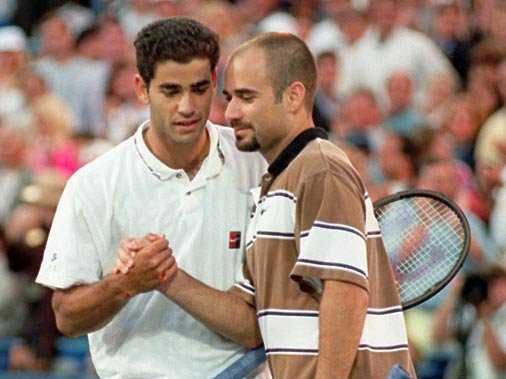

1 – 1995 FINAL: PETE SAMPRAS d. ANDRE AGASSI, 6-4, 6-3, 4-6, 7-5

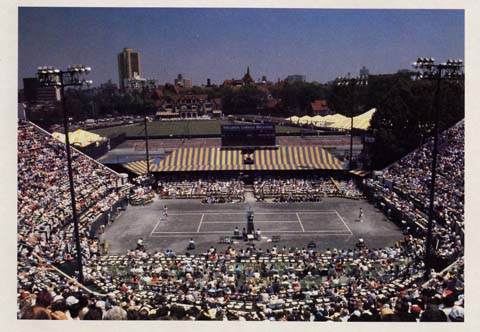

Two men entered Louis Armstrong Stadium as champions in the 1995 U.S. Open final. One left with a career-advancing achievement. The other lost what first appeared to be a career-breaking match… at least for the next three years. To his great credit, Andre Agassi eventually rebounded from this gut-punch loss to his foremost rival.

The 2010 Djokovic-Federer semifinal was huge for Djokovic and crushing for Federer, but Federer had already achieved so much in the sport. The 2010 Nadal-Djokovic final did anything but send the losing player into a tailspin. The 1976 Connors-Borg final and the 1981 McEnroe-Borg final affected the losers and helped the winners, but neither of the winners in those matches didn’t claim more than eight major singles titles.

The 1995 U.S. Open final between Pete Sampras and Andre Agassi managed to do what those four matches couldn’t quite do. This match, probably as hyped as the 1981 McEnroe-Borg final and the 2011 Nadal-Djokovic final (but not any others), felt like a hugely consequential moment at the time. The ’81 and ’11 finals were similar in that regard. Yet, it can be argued that the ’95 Open final wound up carrying more weight in both directions, for the winner and the loser.

Even though Borg lost Open finals in 1976 and 1981, his career stands well above Connors and McEnroe, the two men who denied him in those matches. As for the 2011 final, Nadal suffered in the 2012 Australian Open as a result of his loss to Djokovic in New York. Yet, Djokovic’s momentum didn’t last far beyond that, as Rafa made his stand at Roland Garros in June of 2012.

In 1995, though, Sampras’s win over Agassi marked a clear split in two men’s epic careers. In one match, at one place, at one point in time, Sampras took his career to a lofty plateau and sustained his command over Agassi at the U.S. Open, something he would reinforce with victories in the 2001 quarterfinals (their best match at the Open over the years) and the 2002 final that sent Pistol Pete into retirement as a champion. In that same match at that same frozen moment in history, Agassi’s career plummeted. Sampras (and Agassi’s own shattered mind) caused three years to drift away from Agassi’s career. It wasn’t until 1999 that Agassi regrouped.

Of course, the fact that Agassi did regroup — and magnificently at that — makes the Las Vegan’s career that much more special and admirable in a poignantly human way. Agassi’s post-1999 tennis life marks one of the great third acts (1994 and 1995 marked his second act, not his first) in any hallowed sports career. Yet, for all the amazing things Agassi did as an old man in tennis terms, Sampras forged the far superior career, and while the 1999 Wimbledon final played a role in confirming that reality, the 1995 U.S. Open is what truly caused that reality to unfold.